|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

FAA drone Part 89 remote identification laws are in effect. In this article, we will answer common troubling questions such as:

- What are the requirements for drone pilots?

- How do you know what aircraft are compliant?

- Where can I find a list of remote identification broadcast modules to retrofit my aircraft?

- What happens if I cannot comply? Can I obtain some type of remote identification waiver from the requirement to broadcast?

If any of those questions hit home, this article is for you. But we won’t stop there, we’ll discuss all sorts of various issues related to remote ID so to make this the ultimate guide to Part 89 remote identification.

Note: On September 15, 2023, FAA issued a statement saying “FAA will exercise its discretion in determining how to handle any apparent noncompliance, including exercising discretion to not take enforcement action, if appropriate, for any noncompliance that occurs on or before March 16, 2024—the six-month period following the compliance deadline for operators initially published in the Remote Identification of Unmanned Aircraft final rule, RIN 2120-AL31. The exercise of enforcement discretion herein creates no individual right of action and establishes no precedent for future determinations.”

Table of Contents of Article

- 1 Part 89 Remote Identification Requirements

- 2 How Do I Know If My Aircraft Is Remote Identification Compliant?

- 3 List of Broadcast Modules for Aircraft That Don’t Comply

- 4 Remote Identification Authorizations and Exemptions To Not Comply With Requirements

- 5 How the Remote Identification Requirements Affect Different Groups:

- 6 Different Types of Remote Identification

- 7 What manufacturers need to know about the remote identification rule.

- 8 FAA Accepted Remote Identification Means of Compliance

- 9 Contentious Background of How Remote ID Was Developed by FAA

- 10 Lawsuits Challenging Remote Identification

- 11 Can You Rely on Remote ID? (RID being disabled and spoofed by people)

- 12 Remote Identification Timeline of Events

- 13 Major Changes from Proposed Rule to Final Rule

- 14 Remote Identification Risk Assessments

Part 89 Remote Identification Requirements

The Part 89 Remote Identification regulations are the next incremental step toward further integration of Unmanned Aircraft (UA) in the National Airspace System. In its most basic form, remote identification is described by the Federal Aviation Administration as a “digital license plate” for unmaned aircraft. The FAA views Remote ID (1) as necessary to address aviation safety and security issues regarding drone operations in the National Airspace System and (2) is an essential building block toward safely allowing more complex UA operations.

The final rule establishes Part 89 in Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations. The final rule is in effect. Compliance timeframes and major provisions are summarized below.

Operating Rules for Pilots

Who must comply? Under the final rule, all unmanned aircraft (civil, recreational, police, fire, etc.) that are required to register must remotely identify, and operators have FOUR options (described below) to satisfy this requirement. This is very broad. Yes, even law enforcement must comply. With regards to weight, aircraft 55 pounds and heavier must comply. Those under 55 pounds must comply. For unmanned aircraft weighing 0.55 lbs or less, remote identification is only required if the unmanned aircraft is operated under rules that require registration. Here is where people get confused. An example of this is when you fly a little drone commercially and fly under Part 107. Part 107 requires registration regardless of weight.

Option 1. Fly a Standard Remote ID Unmanned Aircraft:

- Broadcasts remote ID messages directly from the UA via radio frequency broadcast (likely Wi-Fi or Bluetooth technology), and broadcast will be compatible with existing personal wireless devices.

- Standard Remote ID message includes UA ID (serial number of UA or session ID); latitude/longitude, altitude, and velocity of UA; latitude/longitude and altitude of Control Station; emergency status; and time mark.

- Remote ID messages will be available to most personal wireless devices within range of the broadcast; however, correlating the serial number or session ID with the registration database will be limited to the FAA and can be made available to authorized law enforcement and national security personnel upon request.

- The range of the remote ID broadcast may vary, as each UA must be designed to maximize the range at which the broadcast can be received.

Option 2. Fly a Drone with a Remote ID Broadcast Module:

- Broadcast Module may be a separate device that is attached to an unmanned aircraft, or a feature built into the aircraft.

- Enables retrofit for existing UA, and the Broadcast Module serial number must be entered into the registration record for the unmanned aircraft.

- Broadcast Module Remote ID message includes the serial number of the module; latitude/longitude, altitude, and velocity of UA; latitude/longitude and altitude of the take off location, and time mark.

- UA remotely identifying with a Broadcast Module must be operated within visual line of sight at all times.

- Broadcast Module to broadcast via radio frequency (likely Wi-Fi or Bluetooth technology).

- Compatibility with personal wireless devices and range of the Remote ID Broadcast Module message similar to Standard Remote ID UA (see above).

Option 3. Fly at an FAA-Recognized Identification Area (FRIA):

- Geographic areas recognized by the FAA where unmanned aircraft not equipped with Remote ID are allowed to fly.

- Organizations eligible to apply for the establishment of an FRIA include community-based organizations recognized by the Administrator, primary and secondary educational institutions, trade schools, colleges, and universities.

- Must operate within the visual line of sight and only within the boundaries of an FRIA.

- The FAA will begin accepting applications for FRIAs 18 months after the effective date of the rule, and applications may be submitted at any time after that.

- FRIA authorizations will be valid for 48 months, may be renewed, and may be terminated by the FAA for safety or security reasons.

If you need help obtaining an FRIA for your Community-Based Organization or your education institution, contact me.

Option 4. Obtain Part 89 authorization or exemption to NOT have to broadcast

- Multiple groups are interested in this such as :

- Drone light shows with hundreds of drones.

- FPV racers that are weight sensitive or that have issues with the remote ID signals causing control or video feed interference.

- Beyond line of sight drones that are not standard ID but broadcast module remote ID and therefore unable to fly beyond line of sight. See 89.115(a)(2)(ii).

- Law enforcement needing to not broadcast so the bad guys don’t figure out they are being watched.

- Security departments maintaining perimeter security.

- You can obtain a certificate of authorization (COA) or exemption to not have to comply with remote ID. If you need help with one of these, contact me.

- Note that there is a temporary ability for government entities to obtain a quick temporary emergency basis authorization from remote ID.

- FAA can grant this temporary COA in certain situations such as:

- National Defense,

- Homeland security,

- Intelligence gathering, or

- Law enforcement purposes where broadcasting could compromise operational security that could result in injury to law enforcement or civilians, damage to property in the aircraft or on the ground, or failure of the mission.

- Government entities cannot obtain these temporary remote ID authorizations for situations where operational security is not an issue such as:

- Traffic monitoring and enforcement

- Search and rescue

- Maintenance

- Training

- Firefighting

- Over patrols.

- Individual operators must not contact FAA asking for this. Parent agencies, government entities, etc. should contact the FAA to coordinate this. If you are a government entity needing help with this, contact me.

- FAA can grant this temporary COA in certain situations such as:

Part 89 Remote Identification Design and Production Rules for Manufacturers

- Most unmanned aircraft must be produced as Standard Remote ID Unmanned Aircraft and meet the requirements of this rule beginning 18 months after the effective date of the rule.

- Remote ID Broadcast modules must be produced to meet the requirements of the rule before they can be used.

- The final rule establishes minimum performance requirements describing the desired outcomes, goals, and results for remote identification without establishing a specific means or process.

- A person designing or producing a standard UA or broadcast module must show that the UA or broadcast module met the performance requirements of the rule by following an FAA-accepted means of compliance.

- Under the rule, anyone can create a means of compliance. However, the FAA must accept that means of compliance before it can be used for the design or production of any standard remote identification UA or remote identification broadcast module.

- FAA encourages consensus standards bodies to develop means of compliance and submit them to the FAA for acceptance.

- Highlights of Standard Remote ID UA Performance Requirements:

- UA must self-test so UA cannot takeoff if Remote ID is not functioning

- Remote ID cannot be disabled by the operator

- Remote ID Broadcast must be sent over unlicensed Radio Frequency spectrum (receivable by personal wireless devices, ex: Wi-Fi or Bluetooth)

- Standard Remote ID UA and Remote ID Broadcast Modules must be designed to maximize the range at which the broadcast can be received.

Other Provisions in the Remote Identification Final Rule

- Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast (ADS-B) Out and Air Traffic Control (ATC) Transponder Prohibition for UAS

- The final rule amends Parts 91 and 107 to prohibit the use of ADS-B Out or ATC Transponders on UAS unless otherwise authorized by the Administrator, or if flying under a flight plan and in two-way radio communication with ATC.

- ADS-B Out & ATC transponder authorization is likely for large UAS operating in controlled airspace.

- Part 89 prohibits the use of ADS-B Out as a means of meeting remote ID requirements.

- Aeronautical Research

- The rule provides for operators to seek special authorization to operate UA without remote identification for the purpose of aeronautical research or to show compliance with regulations.

- Deviation authority

- The final rule provides a mechanism for the FAA Administrator to authorize deviations from the operating requirements.

- Foreign Registered Civil Unmanned Aircraft Operated in the United States

- The rule allows a UA registered in a foreign country to be operated in the United States only if the operator files a notice of identification with the FAA. This enables the FAA and law enforcement to correlate a remote ID broadcast with a person responsible for the operation of a foreign-registered UA.

How Do I Know If My Aircraft Is Remote Identification Compliant?

You go to the FAA’s declaration of compliance list here. https://uasdoc.faa.gov/listDocs Look up your aircraft. Note that sometimes you might have to search for the aircraft’s model number as opposed to its common name. You might also just have to search by manufacturer name and just scroll through all of the listings. Sometimes manufacturers may have multiple DOCs for the same make/model because different serial number groups were approved. This could be because of design changes. You need to search inside the serial number lists to see which one applies to you.

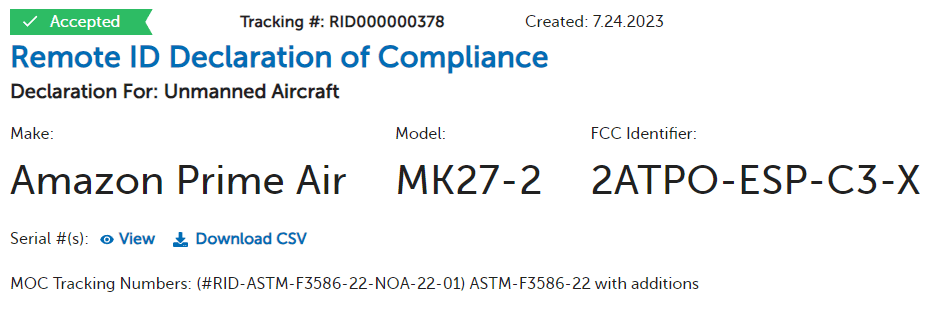

Let’s pull some declarations and explain things.

Here is a standard remote ID declaration of compliance for the Amazon Prime Air MK-27-2 aircraft. The green accepted at the top shows it is still good. If it was rescrinded, it would have a big red “rescinded” marking at the top left. Here is an example of a rescinded DJI DOC. All of the serial numbers approved in this Amazon DOC are in a CSV file. The Means of Compliance (MOC) used was the ASTM standard with FAA additions.

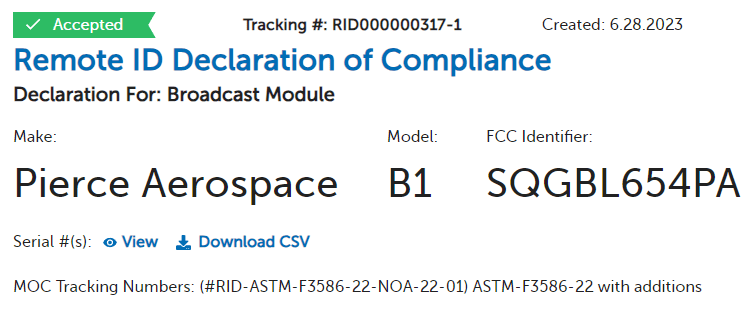

Let’s study what a broadcast module DOC looks like.

At the top it shows it is accepted. It says it is a “Declaration For: Broadcast Module” which differentiates it from a standard ID aircraft. The list of serial numbers is in the CSV file. The MOC was the ASTM MOC with FAA additions.

You should regularly check in to see if your DOCs are good as the FAA has rescinded in the past. Notices are published in the Federal Register. The DJI rescission posted in the Federal Register was fascinating.

On January 19, 2023, the FAA evaluated and accepted a DOC application with the assigned tracking number of RID000000111 appearing to be from DJI for the Mavic Pro Platinum unmanned aircraft. On February 16, 2023, the FAA received communication from DJI stating that the group of products listed in the DOC application with the assigned tracking number RID000000111 were, in fact, not compliant with the performance requirements of part 89. Therefore, DJI requested a rescission of the FAA-accepted DOC with tracking number RID000000111. DJI’s subsequent internal review of the incident determined that the employee listed as the contact on the DOC application no longer had RID certification responsibilities at the time the DOC was submitted, and their employee stated he did not submit the RID000000111 DOC. The FAA is continuing to investigate.

List of Broadcast Modules for Aircraft That Don’t Comply

Your aircraft isn’t compliant? Bummer. I created a list for you of broadcast modules.

- Holy Stone HSRID01

- Blue Mark db121pcb

- Zephyr Systems Module 100

- Dronetag BS

- BlueMark db120

- uAvionix ping RID

- BlueMark db100

- Pierce Aerospace B1

Remote Identification Authorizations and Exemptions To Not Comply With Requirements

You can obtain authorization for the following scenarios.

- You do not want or cannot to comply with:

- Remote identification requirements overall (you do NOT want to broadcast). Entities interested in this would be:

- Drone light show operators not wanting to retrofit all their drones with broadcast modules. Most drone light show aircraft were either custom-built or never built by manufacturers to comply with US remote ID requirements.

- Law enforcement, national security, intelligence gathering, homeland security (border patrol), etc.

- FPV racing.

- People who are in fear for their safety due to people on the ground or their drone getting shot and causing a forest fire in a drought.

- Standard remote identification requirements (because you want to broadcast but don’t meet some requirements for standard remote ID). Here are some examples where I think this might pop up:

- The Declaration of Compliance was rescinded by the FAA and a customer’s fleet is grounded. They figure it’s cheaper to obtain a COA to fly their technically non-compliant aircraft rather than retrofitting all of their fleet with broadcast modules. This is like the drone light show COAs.

- A manufacturer has some bad software and remote identification broadcast fails. This could happen with a bad underlying software update that breaks or erases something. The manufacturer needs a temporary fix for their customers while they push out an update.

- Broadcast module remote identification requirements (because you cannot comply with broadcast module equipment or operational requirements).

- A beyond-line-of-sight drone was retrofitted by a manufacturer with a broadcast module due to issues with the ground controller. They couldn’t do standard ID because they might be using a ground controller from another company or there was no GPS receiver installed in the original controller. The poor customers can’t fly beyond line of sight because 89.115(a)(2)(ii) prohibits a broadcast module aircraft from being flown beyond line of sight.

- Remote identification requirements overall (you do NOT want to broadcast). Entities interested in this would be:

- You want to fly beyond line of sight at an FRIA.

- You want to fly your drone outside of an FRIA.

- You want to fly the drone only for aeronautical research. This could be where you have RF receiving equipment and you need to run silent. You could be developing a military drone that will never be manufactured to broadcast.

- You want to manufacture drones for your own consumption and use them commercially. Your commercial operation is a type of operation you think the FAA will give you authorization for to not comply. It’s burdensome to comply with manufacturing these drones but you can obtain authorization to not comply.

- You are a manufacturer working on type certification while also working on obtaining a Declaration of Compliance approval for your aircraft but nothing is approved yet.

If you do not fall into any of those things, you will need to obtain an exemption from the regulations. Keep in mind that all of the things above can be also exempted. There are pros and cons to each of these. If you need help with an authorization or exemption, contact me. We can discuss a strategy to meet your goals with timing, price, confidentiality, etc.

How the Remote Identification Requirements Affect Different Groups:

Beyond Line of Sight Flyers

You have two types of remote ID: standard ID and broadcast ID. A lot of drones used for beyond line of sight are NOT standard ID. The only alternative is broadcast module ID. Here is the big issue. 89.115 says:

A person operating an unmanned aircraft that is not a standard remote identification unmanned aircraft may comply with the remote identification requirement of § 89.105 by meeting all of the requirements of either paragraph (a) or (b) of this section. . . . (ii) The person manipulating the flight controls of the unmanned aircraft system must be able to see the unmanned aircraft at all times throughout the operation.

If you are BVLOS flying, you need a standard ID drone or you need approval from the FAA to deviate from Part 89. Contact me if you need this.

Drone Light Shows

Unless you want to equip ALL of those drones with broadcast remote identification, you’ll need some authorization. Furthermore, this also creates a safety issue because it greatly increases the noise floor and potentially interferes with command and control of the aircraft. Contact me if you need help with obtaining one of these drone light show remote ID authorizations.

Law Enforcement

I’m guessing law enforcement will want to NOT broadcast if they are flying under Part 107 as civil aircraft.

General Part 107 Operations

You’ll need a standard remote identification aircraft to fly beyond line of sight.

You’ll need remote identification to even fly persistently over large crowds of people.

On top of those things, standard ID transmits the real-time location of the control which opens you up to assault, robbery, harassment, false allegations of trespass/eavesdropping, etc. Broadcast module ID transmits the aircraft take-off location so you launch somewhere and then get to a safe location.

Your privacy was also thrown in the garbage. The FAA didn’t figure out session ID and kicked the can down the road which is evidenced by their statement in the final rule, “The FAA proposed that a session ID would be assigned by a Remote ID USS. Because this rule does not retain the requirement for standard remote identification unmanned aircraft to have an internet connection to a Remote ID USS, the FAA plans to develop an alternative strategy for assignment of session ID to unmanned aircraft operators. . . . FAA will seek public comment on the session ID policy prior to finalizing it.” FlightAware is gonna be jumping all over this like they did with ADS-B.

First-Person View Flyers

- Requires take-off location with GPS which means you need a GPS receiver attached.

- Unless you broadcast, you can only fly at an FAA-recognized identification area (FRIA). Only recognized Community Based Organizations (CBOs) or educational institutions could apply for a FRIA. See 14 CFR 89.205. Basically, your backyard, your neighborhood park, etc. are all off-limits.

- Recreational flying of the under 250 gram aircraft (0.55 pounds) does not have to be registered or transmit remote identification messages. Non-recreational FPV flying would require registration and remote ID even if they were flying under 250 grams.

RaceDayQuads has a very helpful page with much more on this topic. Many people were concerned about the RID regulations prohibiting FPV flying. Here is an excerpt from RaceDayQuads’ page explaining why FPV won’t be prohibited:

Doesn’t the new rules cause havoc for the FPV community since you have to fly within visual line of sight in the FRIAs or with module ID? If a FPV flyer was wearing goggles, how could the drone be within line of sight? They have goggles on ya know!

To answer this, we need to go back into history to understand the FAA’s evolving view of “within visual line of sight” and “able to see” to understand what is going on here.

For many decades model aircraft flew under Advisory Circular 91-57. The FAA started applying the Federal Aviation Regulations to unmanned aircraft and their view on things was evolving.

In 2012, the FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 2012 was passed which created Section 336 that protected model aircraft from being regulated by the FAA. The FMRA defined model aircraft as “flown within visual line of sight of the person operating the aircraft.” P.L. 112-95, section 336(c)(2).

In 2014, the FAA issued a model aircraft interpretation explaining how they thought you should do things, “Based on the plain language of the statute, the FAA interprets this requirement to mean that: (1) the aircraft must be visible at all times to the operator; (2) that the operator must use his or her own natural vision (which includes vision corrected by standard eyeglasses or contact lenses) to observe the aircraft; and (3) people other than the operator may not be used in lieu of the operator for maintaining visual line of sight. Under the criteria above, visual line of sight would mean that the operator has an unobstructed view of the model aircraft. To ensure that the operator has the best view of the aircraft, the statutory requirement would preclude the use of vision-enhancing devices, such as binoculars, night vision goggles, powered vision magnifying devices, and goggles designed to provide a “first-person view” from the model. reducing his or her ability to see-and-avoid other aircraft in the area. Additionally, some of these devices could dramatically increase the distance at which an operator could see the aircraft, rendering the statutory visual-line-of-sight requirements meaningless.” This is all before Part 107 became a law. The FAA was applying the regulations of the time, 91.113 which has a “see and avoid” requirement, to unmanned aircraft because the FAA believed that the FMRA’s “rulemaking prohibition would not apply in the case of general rules that the FAA may issue or modify that apply to all aircraft[.]” like Part 91’s regulations.

In 2016, Part 107 came out with Part 101 subpart E. Part 107 allows FPV flying under 107.31 and 107.33. Here is where people get tripped up. Section 107.31 says: (a) With vision that is unaided by any device other than corrective lenses, the remote pilot in command, the visual observer (if one is used), and the person manipulating the flight control of the small unmanned aircraft system must be able to see the unmanned aircraft throughout the entire flight in order to: . . . . (b) Throughout the entire flight of the small unmanned aircraft, the ability described in paragraph (a) of this section must be exercised by either: (1) The remote pilot in command and the person manipulating the flight controls of the small unmanned aircraft system; or (2) A visual observer.” (Emphasis mine).

In 2018, the FAA Reauthorization Act of 2018 hit the delete button on Section 336 and replaced it with now 49 USC 44809. This caused issues seeing that Part 101 subpart E was still on the books, but Section 44809 overruled it. Most recreational flyers desire to fly within the exception for limited recreational operations listed in 49 USC 44809 which says in (a)(3), “The aircraft is flown within the visual line of sight of the person operating the aircraft or a visual observer co-located and in direct communication with the operator.” (Emphasis mine).

In 2019, the FAA cleaned things up by withdrawing the 2014 model aircraft interpretation which said FPV flying with goggles can’t see and avoid.

On 12/11/2020, the FAA withdrew Part 101 subpart E as a regulation because it caused confusion and was overruled by 49 USC 44809 which came from the FAA Reauthorization Act of 2018.

CURRENTLY, you either fall into 49 USC 44809 which is for a very narrow group of recreational flyers (not all recreational flyers) or you fall into Part 107 which is for non-recreational flyers. That’s it. Remote ID in Part 89 applies to all unmanned aircraft, with some exceptions. All FPV flyers over 250 grams, flying in the national airspace of the United States, will have to do broadcast module remote ID, standard ID, fly in a FAA Recognized Identification Area (FRIA). FRIAs are granted only to recognized Community Based Organizations or educational institutions. Your backyard, friends’ yard, local park, etc. are most likely NOT going to be in a FRIA so FPV flyers flying a 250+gram drone are stuck doing standard ID (SID) or broadcast module ID (BMID).

Broadcast module ID allows for retrofitting aircraft but BMID has requirements:

“A person operating an unmanned aircraft that is not a standard remote identification unmanned aircraft may comply with the remote identification requirement of § 89.105 by meeting all of the requirements of either paragraph (a) or paragraph (b) of this section.

(a) Remote identification broadcast modules. Unless otherwise authorized by the Administrator, a person may operate an unmanned aircraft that is not a standard remote identification unmanned aircraft if all of the following conditions are met:

(1) Equipage.

(i) The unmanned aircraft used in the operation must be equipped with a remote identification broadcast module

. . . .

(2) Remote identification operating requirements. Unless otherwise authorized by the Administrator, a person may operate an unmanned aircraft under this paragraph (a) only if all of the following conditions are met:

. . . .

(ii) The person manipulating the flight controls of the unmanned aircraft system must be able to see the unmanned aircraft at all times throughout the operation.

. . . .

(b) Operations at FAA-recognized identification areas. Unless otherwise authorized by the Administrator, a person may operate an unmanned aircraft without remote identification equipment only if all of the following conditions are met:

. . .

(2) The person manipulating the flight controls of the unmanned aircraft system must be able to see the unmanned aircraft at all times throughout the operation.” (Emphasis mine).

So how do we figure out what this “able to see” means in Part 89? Do FPV goggles void that? If I am wearing goggles, doesn’t that mean I’m not ABLE to see?

The remote ID notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM) was attempting to define visual line of sight in Section 1.1. But that didn’t make it into the final rule. The final rule’s preamble said, “the FAA has determined not to adopt a definition for ‘visual line of sight’ in this rule.” They did not want to lock one definition in for ALL types of operations which may in the future have different definitions of visual line of sight, so they abandoned a one definition scenario. No help there. We need to look elsewhere.

In the remote ID NPRM, the FAA proposed the definition of visual line of sight from 107.31; therefore, that would be the most appropriate, and only other place to look, to identify how to define this term. Context of 107.31 helps bring to light what is meant. Section 107.31 says, “(a) With vision that is unaided by any device other than corrective lenses, the remote pilot in command, the visual observer (if one is used), and the person manipulating the flight control of the small unmanned aircraft system must be able to see the unmanned aircraft throughout the entire flight in order to: . . .(b) Throughout the entire flight of the small unmanned aircraft, the ability described in paragraph (a) of this section must be exercised by either: (1) The remote pilot in command and the person manipulating the flight controls of the small unmanned aircraft system; or (2) A visual observer.” (Emphasis mine). Here is a comparison.

89.105 (Broadcast Module Remote ID or FRIA) 107.31 “The person manipulating the flight controls of the unmanned aircraft system must be able to see the unmanned aircraft at all times throughout the operation.” “the person manipulating the flight control of the small unmanned aircraft system must be able to see the unmanned aircraft throughout the entire flight in order to:” For 107.31, there is the ability to see by taking off the goggles and see the unmanned aircraft. The ability is primarily a distance and human capability number. The larger the drone, the further away you could fly. The smaller the drone, the shorter the distance you could fly it away. Now 107.31(b) says the ability must be getting exercised by the RPIC or VO. Section 44809 and Part 89 do not have any such exercising of the ability requirement, just the ability.

In the area where the FAA discussed visual line of sight in the preamble of the final rule, it said, “FAA Response: As noted, the FAA has determined not to adopt a definition for ‘visual line of sight’ in this rule. The FAA recognizes that the concept of visual line of sight allows for variation in the distance to which an unmanned aircraft may fly and still be within visual line of sight of the person manipulating the flight controls of the UAS or the visual observer. The FAA believes this is appropriate given the performance-based nature of current UAS regulations.” (Emphasis mine). The ability to see the drone is what limits the distance you can fly away. Ability determines distance.

If we read part 89 and 107 to be harmony, Part 89 does not restrict FPV racers from using goggles as long as the person manipulating the controls is “able to see the unmanned aircraft at all times” and keeps the unmanned aircraft “within the visual line of sight of the person operating the aircraft or a visual observer co-located and in direct communication with the operator.”

Different Types of Remote Identification

Broadcast Module Identification

Here is what the FAA said:

-

Broadcast Module may be a separate device that is attached to an unmanned aircraft, or a feature built into the aircraft.

-

Enables retrofit for existing UA, and Broadcast Module serial number must be entered into the registration record for the unmanned aircraft.

-

Broadcast Module Remote ID message includes: serial number of the module; latitude/longitude, altitude, and velocity of UA; latitude/longitude and altitude of the take off location, and time mark.

-

UA remotely identifying with a Broadcast Module must be operated within visual line of sight at all times.

-

Broadcast Module to broadcast via radio frequency (likely Wi-Fi or Bluetooth technology).

-

Compatibility with personal wireless devices and range of the Remote ID Broadcast Module message similar to Standard Remote ID UA (see above).

The idea is you attach some approved broadcast module to your drone to retrofit it so it could be compliant. The FAA thought, “Hey, it’s equivalent so we do not need to send out a supplemental notice of proposed rulemaking to alert everyone to this change and to receive feedback.” If they did send out a supplemental NPRM, they could have received a response saying adding a broadcast module to a drone and controller introduces additional safety issues. Basically, attaching a second radio transmitter on a drone in very close proximity raises serious technical issues of radio frequency interference due to software filters being unable to filter and the electromagnetic field issues where the 2nd set of electronics in close proximity can cause issues with aircraft’s electronic flight controls.

Standard Identification

The FAA said:

-

Broadcasts remote ID messages directly from the UA via radio frequency broadcast (likely Wi-Fi or Bluetooth technology), and broadcast will be compatible with existing personal wireless devices.

-

Standard Remote ID message includes: UA ID (serial number of UA or session ID); latitude/longitude, altitude, and velocity of UA; latitude/longitude and altitude of Control Station; emergency status; and time mark.

-

Remote ID message will be available to most personal wireless devices within range of the broadcast; however, correlating the serial number or session ID with the registration database will be limited to the FAA and can be made available to authorized law enforcement and national security personnel upon request.

-

Range of the remote ID broadcast may vary, as each UA must be designed to maximize the range at which the broadcast can be received.

If you want to fly BVLOS, you’ll need this. It also presents a safety hazard in that your controller location is always being broadcasted in real-time. Comon! That isn’t fair. A person can’t keep looking over his shoulder all the time for the bad guys who are looking to rob him when he is busy waiting for the FAA to ambush him.

Limited Remote Identification (Killed in Final Rule)

It was in the notice of proposed rulemaking but was killed. There were multiple reasons the FAA killed it. I won’t get into them all now but two important things are that the altitude of the aircraft and controller were both derived from a barometric altimeter (not from GPS) which means all sorts of aircraft and ground control stations would have to be upgraded with hardware. The other important thing is limited remote identification was originally transmitted using the transmitters located already in the ground control station and the aircraft. You would have at least 1 transmitter in the drone and at least 1 in the ground control station.

The FAA figured they could come up with an equivalent idea called broadcast module ID that would satisfy some of the security concerns. They look similar, but they are not.

Network Remote Identification (Killed in Final Rule)

Yes, network remote ID was killed in the final rule but below is what I was able to piece together to see how far the FAA was going to be “Big Brother” and monitor us. Massive violations of the 4th Amendment. My theory on this is that the FAA decided to scrap it and just let federal, state, and local law enforcement set up receivers to just log all the flights. Read the secret ConUse document I managed to obtain that the FAA secretly gave out to the big companies in those closed-door meetings: T Mobile, Airbus, Amazon, Skyward (Owned by Verizon), etc.

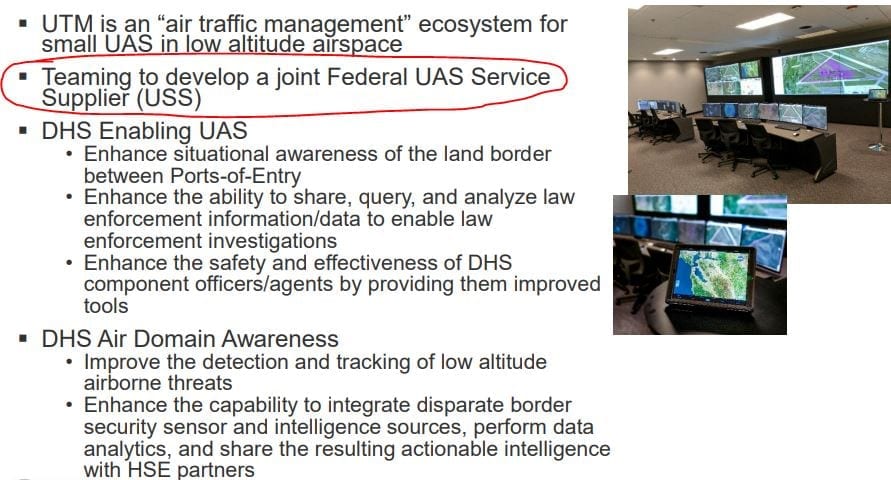

So do we just forget about this? Just check out what shocking things I uncovered about how the FAA, DHS, and UTM were/are all interconnected and how this all currently intersects with the 4th Amendment. With all of that in mind…..put your 4th Amendment glasses on and read what I’m about to say.

Remote ID is part of the Unmanned Aircraft Traffic Management System (UTM). FAA, NASA, DHS, DOD have been working on this. FAA, DHS, and DOD have a teaming agreement. DHS is going to be a federal Unmanned Aircraft Service Supplier (USS). While the FAA may be collecting a lot of the data, DHS could query things in the system. The FAA in explaining their Concept of Operations (CONOPs) regarding UTM, said the following:

- “Flight Information Management System/FIMS FIMS is an interface for data exchange between FAA systems and UTM participants. FIMS enables exchange of airspace constraint data between the FAA and the USS Network. The FAA also uses this interface as an access point for information on active UTM operations. FIMS also provides a means for approved FAA stakeholders to query and receive post-hoc/archived data on UTM operations for the purposes of compliance audits and/or incident or accident investigation. FIMS is managed by the FAA and is a part of the UTM ecosystem.”

- DHS’s Air Domain Awareness Program is somehow connected to FIMS as a USS. See this Powerpoint presentation.

- “Air Domain Awareness is understanding everything that is in the air around you . . . Includes all manned and unmanned aircraft”

- “DHS is teaming with FAA and DOD to evaluate air domain awareness and counter UAS systems in real world situations”

- The UTM CONOPS says, “The FAA provides services to certain federal public entities in support of public safety and security needs; services may include provision of portals designed to facilitate automated information exchanges and queries to the USS Network for authorized data. Local, state, tribal and federal public entities may have dedicated portals external to the FAA by which they can request and receive authorized information; USSs meet applicable security requirements and protocols when collecting and provisioning data to such entities. Authorization and authentication between entities, using IATF compliant identities, ensure data is provisioned to those permitted to obtain it. Authorized entities utilize USS Network discovery services to identify individual USSsfrom which to request and receive data commensurate with access credentials. USSs must be (1) discoverable to the requesting agency, (2) available and capable to comply with issue request, and (3) a trusted source as mitigation/enforcement actions may be taken as a result of the information provided.“

- DHS’s Air Domain Awareness Program is somehow connected to FIMS as a USS. See this Powerpoint presentation.

- “The FAA establishes requirements and response protocols to guard NAS systems and the public against associated security threats. The FAA uses UTM data (e.g., intent, RID messages) as a means of traceability to (1) ensure Operators are complying and conforming to regulatory standards, (2) identify and hold accountable those who are responsible during accident/incident investigations, and (3) inform other NAS users, if needed, of UAS activity in the vicinity of the airspace in which they are operating. The FAA can use near-real time data from UTM to address security needs with respect to operations conducted under ATM, including managing off-nominal and exigent circumstances. They use archived data as a means to analyze UTM operations and ensure NAS needs and safety objectives are being met. The FAA can also use UTM data to notify federal entities of security threats. The FAA leverages the GRAIN and the IATF policies to ensure the integrity and authenticity of the information received from all UTM stakeholders. “

- “Local, state, tribal and federal entities (e.g., state police, Federal Bureau of Investigation, DHS) require access to UTM data to inform responses to local or federal complaints and safety/security incidents, and the conduct of investigations. Appropriate data access limitations are set by the FAA for individual federal and public/public safety entities (e.g., public information, classified information). Depending on the nature of the safety or security situation, historical or near-real time information may be needed. UTM data deemed publicly-accessible (e.g., RID messages) may be obtained by the general public through thirdparty services/applications and/or the government. UTM data that is not publicly-accessible (e.g., Operator contact information) is managed and provided based on the need to know, the credentials, and the level of access-to-information authorized for the requestor using identities issued compliant to the IATF policies.”

- “Operators must satisfy FAA-stipulated data archiving and sharing requirements to support safety and security. Stakeholders may need information on active UTM operations for the purposes of aircraft separation and identification of UAS affecting air/ground activities, among other things, such that Operators respond to requests from authorized entities in near-real time; an example of such information is RID messages. Operators are required to archive certain data to support post-flight requests by authorized entities with a need to know (e.g., FAA, public entities), as previously noted; examples of such data may include operation intent, 4D position tracks, reroute changes to intent, and off-nominal event records (e.g., rogue UAS).”

Yes, network remote identification was killed in the final rule. But was DHS disconnected from as a USS from the FAA’s FSIMS database? Did they have access in the past? What access were they ever given? Is DOJ or DOD presently connected to FSIMS in any capacity? What records did any of them search? Did they have access to the LAANC, Drone Zone Accounts, Part 48 registration database with associated information, or any other databases?

How does this work into the digital investigations unit of the FAA? The FAA also has been developing the UAS Digital Investigations (UAS DI) Program. Here are the CONOPs for this FAA office.

What manufacturers need to know about the remote identification rule.

If you want to get your aircraft issued a Declaration of Compliance (DOC), here is the FAA Advisory Circular on it.

If you are a manufacturer, you can propose your own Means of Compliance (MOC) which future DOCs can be issued under. This is a really important point. You don’t have to go with the current ASTM standard. You could propose and go through the process to get your proposed MOC accepted. It could be more optimized for your product or offer something that is presently not offered such as network remote identification or session ID to provide privacy.

Note that there are certain exceptions for home-built drones, drones of the U.S. Government, drones for aeronautical research and development or to show compliance with the regulations, or drones under 0.55 pounds. See 14 CFR 89.501.

If your aircraft cannot be retrofitted, you or your customers can obtain authorizations or exemptions for a solution.

If you need help with any of these solutions, contact me.

FAA Accepted Remote Identification Means of Compliance

On August 11, 2022, the FAA published the acceptance of the ASTM remote ID standard ….kinda. Interestingly, the FAA did not choose to accept the ASTM rule alone but just added its own set of requirements. What’s the point of ASTM standards if the FAA just tacks on whatever they want onto any standard? What’s the purpose of rulemaking if the FAA just tacks on extra requirements onto these standards? Here are the FAA additions:

“The FAA-accepted MOC provided in this policy therefore is comprised of ASTM F3586-22 with the following additions:

1. The remote identification system shall protect the part 89-required broadcasted message from being altered or disabled by any person.

2. The remote identification system shall incorporate techniques or methods that reduce the ability of any person to physically and functionally modify or disable any aspect or component of the remote identification system that could impact compliance with the remote identification rule.

3. In applying Section 7.5.2 of ASTM F3586-22, the applicant shall determine whether masking the specified items from user input adequately provides the functional tamper resistance protection specified by this means of compliance, and if it does not, shall incorporate additional functional tamper resistance techniques or methods in accordance with this means of compliance.”

The FAA will over time add more of these means of compliance. You can check the current list of remote ID means of compliance here.

Each Declaration of Compliance will explain which Means of Compliance was used.

If you want to create your own means of compliance (as a manufacturer or for other reasons), the FAA has an entire Advisory Circular explaining this process.

Contentious Background of How Remote ID Was Developed by FAA

The FAA was not honest and open about what happened in the creation of remote ID.

Ex-Parte Regulations and FAA NPRM Developments

It was literally a house ex parte. But this is kinda illegal. The FAA attorneys know that. More on that later but let’s first focus on the law. I put in bold the really important points.

49 CFR §5.19 Public contacts in informal rulemaking.

(a) Agency contacts with the public during informal rulemakings conducted in accordance with 5 U.S.C. 553.

(1) DOT personnel may have meetings or other contacts with interested members of the public concerning an informal rulemaking under 5 U.S.C. 553 or similar procedures at any stage of the rulemaking process, provided the substance of material information submitted by the public that DOT relies on in proposing or finalizing the rule is adequately disclosed and described in the public rulemaking docket such that all interested parties have notice of the information and an opportunity to comment on its accuracy and relevance.

(2) After the issuance of the NPRM and pending completion of the final rule, DOT personnel should avoid giving persons outside the Executive Branch information regarding the rulemaking that is not available generally to the public.

(3) If DOT receives an unusually large number of requests for meetings with interested members of the public during the comment period for a proposed rule or after the close of the comment period, the issuing OA or component of OST should consider whether there is a need to extend or reopen the comment period, to allow for submission of a second round of “reply comments,” or to hold a public meeting on the proposed rule.

(4) If the issuing OA or OST component meets with interested persons on the rulemaking after the close of the comment period, it should be open to giving other interested persons a similar opportunity to meet.

(5) If DOT learns of significant new information, such as new studies or data, after the close of the comment period that the issuing OA or OST component wishes to rely upon in finalizing the rule, the OA or OST component should reopen the comment period to give the public an opportunity to comment on the new information. If the new information is likely to result in a change to the rule that is not within the scope of the NPRM, the OA or OST component should consider issuing a Supplemental NPRM to ensure that the final rule represents a logical outgrowth of DOT’s proposal.

I have no idea how the FAA complied with the regulations above during all of the stuff below….such as during the secret FBI academy remote ID demo where the FAA booklet literally says, “Brief summary of demonstration and Q&A” Drone Responders, Pierce Aerospace, NFL security and a bunch of state and local law enforcement went to this special meeting. Why did Drone Responders get to go to this secret meeting but not AMA, AUVSI, or anyone else?

What about all of the other people who applied to be part of the remote ID cohort but didn’t get chosen like GE, Kittyhawk, etc.? The FAA never gave them an opportunity to be included.

With all of these regulations in mind, keep reading below to see if FAA violated any of them.

Remote Identification Cohort

The FAA also did all sorts of stuff with 8 companies working on network ID. This was all done privately. Here are the actual memorandum of understanding (MOU) documents the FAA signed in conjunction with Airbus, Airmap, Amazon, Intel, Onesky, Skyward, T-Mobile, and Wing

If you don’t believe those are true, see this Certification by the FAA saying these MOUs are true.

The FAA picked 8 companies to enter into agreements with to work on remote ID AFTER the remote ID NPRM was published.

Remember 5.19(a)(2) “After the issuance of the NPRM and pending completion of the final rule, DOT personnel should avoid giving persons outside the Executive Branch information regarding the rulemaking that is not available generally to the public.” The MOUs all said the FAA would provide a ConUse document.

“The FAA will: i. Provide access to data sets, ConUse document, draft Performance Rules and ICD. i. Provide subject matter expert review and advice to proposed technology products, concepts, equipment, software, and other related activities.”“A^3 by Airbus, LLC will: i. Participate in monthly meetings (nominally 2 days in duration) in person in the Washington, D.C. area. ii. Send 2-3 representatives from its organization to each meeting referenced in Section 6(c)(i) of this MOU. Representatives that A^3 by Airbus, LLC provides for these meetings must possess the demonstrated capability to cover strategic, technical, and/or legal aspects of Remote ID.”

Here is the Concept of Use of for Network ID.

Here is the certificate of true copy of the Concept of Use document.

None of this was disclosed in the rulemaking docket

5.19(a)(1) says, “DOT personnel may have meetings or other contacts with interested members of the public concerning an informal rulemaking . . . , provided the substance of material information submitted by the public that DOT relies on in proposing or finalizing the rule is adequately disclosed and described in the public rulemaking docket such that all interested parties have notice of the information and an opportunity to comment on its accuracy and relevance.

The MOUs called for meetings with the Cohort where representatives would be meeting to discuss network ID. Information DID go from these 8 companies to the FAA. Here is the agenda, Powerpoint Presentation for the meeting, and the minutes of the meeting explaining what the companies and FAA talked about.

The MOUs have a lot of troubling statements (note that all 8 companies appear to have the same language in their respective MOUs with the FAA). I can’t figure out how any of these points could be done with the 8 companies submitting information to the FAA without the FAA relying on for network ID:

- “The purpose of this Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) is to establish a working relationship between (FAA) and A^3 by Airbus LCC that will facilitate a collaborative working environment for the development of a technical and legal framework for initial prototyping and testing that will inform a national capability for Remote ID Unmanned Aircraft System (UAS) Service Suppliers (UAS) future for Remote Identification (Remote ID).”

- “The FAA, working with the selected industry cohort, intends to build out a feature set and hold a prototype evaluation. The FAA also intends to evaluate the features in the prototype, address findings, and then roll the features out in a larger evaluation.”

- “Apply collaborative problem solving among FAA and USS (e.g. virtual and in-person workshops) to identify sUAS information sharing needs, assess experience data collected from demonstrations, and recommend system enhancements.”

- “Demonstration collaboration phase: Establish collaborative problem-solving among FAA, other government entities, and industry cohort to address sUAS Remote ID information and data sharing needs, assess experience data collected from demonstrations, and recommend system enhancements.”

- “Alternative approaches, technology solutions, development models, business models, evaluation paths, scaling strategies, etc., for information sharing[.]”

5.19(a)(4) says, “If the issuing OA or OST component meets with interested persons on the rulemaking after the close of the comment period, it should be open to giving other interested persons a similar opportunity to meet.” Did you guys invite Kittyhawk, GE, or any of the others who applied? No.

5.19(a)(5) says, “If DOT learns of significant new information, such as new studies or data, after the close of the comment period that the issuing OA or OST component wishes to rely upon in finalizing the rule, the OA or OST component should reopen the comment period to give the public an opportunity to comment on the new information.” Instead of just following the regulations, the FAA just says in the final remote ID rule:

It has become apparent to the FAA that Remote ID USS may struggle in facing significant technical and regulatory requirements that go beyond existing industry consensus standards. Early in 2020, the FAA convened a Remote ID USS cohort to explore developing the network solution that is necessary to implement the proposed network requirements. The cohort identified several challenges with implementing the network requirements, which the FAA acknowledges it had not foreseen or accounted for when it proposed the network solution and Remote ID USS framework. For example, the cohort raised the challenge of developing and issuing technical specifications to govern remote identification interoperability when producers of UAS have not yet designed UAS with remote identification.

So how many legal violations did you spot?

O but there’s more!

Secret Remote ID Demo at FBI Training Academy

We found about this because the FAA published a comment here disclosing the existence of this secret demo. https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=FAA-2019-1100-53261

The Public Was Not Invited and FAA forced attendees to sign a form promising to not tell you. “I will NOT discuss, divulge, or disclose any Information to any unauthorized person or entity. I will safeguard and prevent the unauthorized disclosure of Information in accordance with all applicable statutes, regulations, and orders. I will return all Information and all copies and reproductions thereof upon request of the FAA.” Just read the Remote ID Demo at FBI Academy Acknowledgement Form

Here is the document given out to attendees. Remote ID Demo at FBI Academy Logistics Book_final

More Ex Parte Events

Here are more examples of things being done NOT on the record, or according to the law, after the notice of proposed rulemaking.

- FAA sent out a request for information (RFI) on in March 17, 2020 (NPRM on remote ID closed March 2) to try and obtain answers on how “low altitude manned aviators. . . could participate in Remote ID, access data from the Remote ID USSs, or otherwise benefit from the Remote ID information being transmitted from UAS.” Multiple groups responded but none of those comments have been disclosed. The RFI said, “Responses to this RFI will not be included in the official docket of the NPRM.” On October 22, 2020, Jay Merkle did a presentation to the Drone Advisory Committee which said that they had 30 responses to this RFI. The FAA thought they “missed the mark when communicating what [they] were looking for in the RFI so they wanted to take a second chance at this and asked the Drone Advisory Committee explore this opportunity and make some recommendations. In the 30 responses, the pilot organizations said they see “dubious benefits:

- UASs have primary responsibility to avoid manned-aircraft.

- RID is security-centric; it may be inadequate to affect safety.

- Adding RID receiving capability would be an additional expense burden to low-level aircraft pilots.

- Low-level pilots are especially concerned with task saturation (e.g., avoiding obstructions & being distracted from the mission).

- Any solutions should integrate with current avionics (EFB, ADS-B).”

- FAA Contract to NUAIR for Remote ID Testing as part of UPP Phase 2.

- 12/17/2020- Jay Merkle (head of FAA UAS Integration Office) sent out a letter to all the tribal leaders. The FAA posted this in the docket.

Did Anyone Try and Stop the Ex Parte Fiesta?

The issue is the ex parte broke out AFTER the comment period closed.

Did anyone tell the FAA about this? Well the FAA attorneys knew. We didn’t have to tell them. (Kathryn Inman who is an FAA attorney was the author of the PDF for the secret FBI academy dem0.) That’s why the FAA posted to the docket TWICE to appear like they were complying with the regulations. ( FBI academy remote ID demo and the letter to all the tribal leaders.)

Tyler Brennan of RaceDayQuads LLC did let the FAA and DOT know. Here is his meeting he did with OIRA, FAA, and DOT. Tyler’s submission for the meeting is helpful in understanding why ex parte is really bad:

This is being submitted as it relates to the FAA’s rulemaking activities in adopting a Final Rule based on the NPRM published on December 31, 2019 that provided for public comment until March 2, 2020 but otherwise denied an extension of that comment period.

The FAA has repeatedly engaged in ex parte conversations, meetings, and other communications with the public, government entities, and businesses on the subject of the rulemaking after the NPRM was filed. These activities suggest that communications made privately may or will influence the agency in its Final Rule.

These communications, whether or not having actual influence, prevent the public from being able to reply effectively to the information that was presented privately to the FAA so the FAA could make a fully informed decision affecting the safety and security of the national airspace. It is possible someone in the public could have pointed out some serious life-threatening safety and security flaws that were not previously identified and to forgo this opportunity is arbitrary, capricious, and an abuse of discretion.

Furthermore, the Administrative Procedures Act and the Due Process Clause requires notice; however, we have no notice of what has been presented to the FAA or relied on privately by the FAA which made its way into the final rule.

Not disclosing everything creates the appearance there is one administrative record for the public and this court and another for the FAA. The mere appearance of ex parte raises questions as to whether the final rule was based upon public comments or secret meetings and secret documents. The FAA just needs to make some public argument for the reason why they arrived at their decisions while keeping secret the true primary reason. Communications outside the record seriously frustrate any meaningful judicial review as judges will not ever know what was really relied upon in deciding. This also frustrates any review under the Congressional Review Act.

This raises serious questions of fairness. The undermining of the fairness of the rulemaking process erodes the FAA’s ability to protect the safety of the national airspace. Many individuals will feel victimized and disenfranchised and therefore justified in not complying with the rules. How is anyone supposed to respect the FAA when the FAA is clearly violating their own rulemaking procedures?

Such improper and unfair ex parte contacts include, but are not limited, to the following actual related out-of-record contacts: the remote ID cohort, the secret meeting at the FBI Academy, and Jay Merkle’s presentation at the Drone Advisory Committee.The final shaping of the rules may have been by compromised among the contending industry forces, rather than by exercise of the FAA’s independent discretion for the public interest.

We are asking that the FAA pause the rulemaking, disclose all of the ex parte events with summaries of those discussions, disclose all of the ex parte documents, allow the public to comment, and then proceed ahead.

Lawsuits Challenging Remote Identification

RaceDayQuads filed a lawsuit. My article on the case is here. RaceDayQuads v FAA. Unfortunately, the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeal was not troubled by the FAA actions and chose to uphold the regulations as legal.

Some of the legal issues we raised in the case are still outstanding and could be raised in future litigation/criminal prosecution.

Can You Rely on Remote ID? (RID being disabled and spoofed by people)

Remote ID is touted as a solution to keep people accountable. Sure. It will work on unaware/clueless individuals who purchase a standard ID drone and then go fly it inappropriately.

To a determined and smart actor, it won’t work. Here is why…..there is information online explaining how to disable or spoofing remote ID.

This has lead to all sorts of tutorials online to turn off remote ID. Here is one that showed up in a forum.

There is also a tutorial on spoofing remote ID. https://www.suasnews.com/2023/07/how-to-spoof-remote-id-squidrid/

The motivation for turning off remote ID is not always criminally motivated. And because of this, I suspect there will always be a growing library of knowledge on the internet contributing to disabling /spoofing remote ID.

1. Ukraine Conflict Causing People to Turn Off Remote ID

In Ukraine, DJI’s Aeroscope has been used by both sides of the conflict to identify DJI drones used by the other side.

A primer from a Russian fighter on how to use DJI’s Aeroscope. pic.twitter.com/BWIwl3rIh9

— Faine Greenwood (@faineg) December 13, 2022

There are stories of drone operators using a DJI and then out of no where an artillery barage comes in on their position. Clever operators hacked their drones and…get this….put in the GPS coordinates of their enemy’s position resulting in the enemy’s artillery doing an artillery strike on their own troops.

2. Domestic operators fearful of crazy shotgun carrying rednecks/Karens.

I can say I get phone calls where drones are being shot down. FAA and law enforement are useless to protect people. The FAA ignored these comments in the remtoe ID rulemaking. It’s a matter of self-protection and putting food on the table of the family as the primary motivation of this group.

Imagine if a Rough Redneck and Krazy Karen puts a hole in a drone which leads to a crash and fire on the ground. You can end up with a large fire happening. This isn’t hypotehtical. Consider these documented real world examples of a crash leading to a large fire:

- Three University of Colorado Boulder researchers conducting weather studies were operating a drone in the Table Mountain Radio Quiet Zone, Boulder County officials said. The aircraft crashed at a high rate of speed causing the lithium battery to catch on fire and spread to the surrounding area. . . . The wildfire quickly grew to about 52 acres, forcing evacuations which have since been rescinded.” Source.

- “In June, a drone motor conked out while the vehicle was transitioning from a vertical climb to forward motion. The automatic safety feature designed to land the machine in such instances didn’t work. The aircraft flipped upside down, and a stabilizing safety function also failed. “Instead of a controlled descent to a safe landing, [the drone] dropped about 160 feet in an uncontrolled vertical fall and was consumed by fire,” the FAA wrote in a report on the incident. The ensuing blaze scorched 25 acres and was extinguished by the local fire department. Insider previously reported some of the incident’s details and last week published a report on the high costs of Amazon drone delivery.” Source.

- “An unmanned aircraft crashed in an agricultural field on Saturday, May 14, sparking two small fires. . . . Baumgart said when his crew arrived on scene, they found an unmanned aircraft down in the field. The aircraft had sustained major damage, and one of the aircraft’s wings was a couple hundred yards away from where the body of the aircraft made impact. . . . The two small fires were isolated to the aircraft’s batteries. Baumgart said the location was mostly dirt, and with the fires isolated to the batteries – it was minimal and the Winters Fire unit was able to put it out.” Source.

This group will just turn off remote ID for fear of being shot or their drone being shot and catching everything on fire.

Remote Identification Timeline of Events

This timeline is very important so you can see what was happening overall during the rulemaking process. Pay attention to what was happening quietly with network ID.

- December 20, 2018, FAA posted a RFI for remote-id cohort.

- December 27, 2019, new final rule of DOT rulemaking regulations was published. 49 CFR 5.17(a)(2) & (4) says, “(2) After the issuance of the NPRM and pending completion of the final rule, DOT personnel should avoid giving persons outside the Executive Branch information regarding the rulemaking that is not available generally to the public. . . (4) If the issuing OA or OST component meets with interested persons on the rulemaking after the close of the comment period, it should be open to giving other interested persons a similar opportunity to meet.”

- December 31, 2019, NPRM of remote ID published.

- January 2020- all the Remote ID cohort MOUs were signed. My theory is this was all rushed to get all signed prior to the 1/27 effective date of the new DOT rulemaking regulations.

- January 27, 2020, new DOT rulemaking regulations went into effect.

- February 26-27, 2020, Ex parte meeting on remote ID with remote ID cohort. Technical Interchange Meeting #1 in Arlington Virginia with FAA.

- March 2, 2020, NPRM COMMENT PERIOD CLOSES

- March 17, 2020- FAA sent out a request for information (RFI) on figuring out how manned aircraft benefit from

- March 24-25, 2020, Technical Interchange Meeting #2 with remote ID cohort done via Zoom. They discussed the ASTM remote ID standard.

- April 6, 2020 – County of Oneida NY (aka NY Test Site) awarded UPP Phase 2 contract to work on remote ID.

- April 15, 2020 – DOT IG’s Office published a report showing FAA lacked adequate security for Drone Zone and LAANC systems.

- April 28-29, 2020, Technical Interchange Meeting #3 with remote ID cohort done via Zoom.

- May 5, 2020 – FAA put out a press release regarding the cohort being selected. (The MOUs were signed in January).

- May 8, 2020 – FAA had to send out a “clean up” email regarding the 5/5 press release.

- “1 Remote ID Cohort Information

Thanks for the questions we received after yesterday’s press release on the Remote ID Cohort. To clarify, the Cohort is not part of the decision-making process for the proposed Remote ID rule final rule. The Cohort will help the FAA develop technology requirements for other companies to develop applications needed for Remote ID. The comment period on the Remote ID Notice of Proposed Rulemaking closed on March 2, 2020, and the FAA is reviewing the more than 53,000 comments.

If you are a member of the media, contact us at [email protected] and a public affairs specialist will respond.

If you are a drone operator with questions about Remote ID, or any other drone-related question, please email [email protected] or call 844-FLY-MY-UA.”

- “1 Remote ID Cohort Information

- May 27, 2020 – Technical Interchange Meeting #4 with remote ID cohort on OAuth in Remote ID USS Data Exchanges via Zoom.

- June 29, 2020 Technical Interchange Meeting #5 on Zoom. Email says, “Q&A time with an FAA Executive concerning recent remote ID strategic decisions.”

- September 17, 2020, FAA secret remote ID demonstration at FBI training academy with federal, state, and local, law enforcement and some civilian entities like Drone Responders, NFL security, and Pierce Aerospace.

- December 17, 2020- Jay Merkle (head of FAA UAS Integration Office) sent out a letter to all the tribal leaders.

- December 28, 2020- DOT released a press release on the remote ID along with the draft final rules.

- January 15, 2021 – the Federal Register posting of the final rule was published.

- March 10, 2021, Federal Register posting that the compliance date of remote id is moved from March 16 to April 21.

- July 29, 2022, D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals delivers opinion upholding the remote ID laws.

- September 16, 2022, deadline for manufacturers to comply with remote ID standards when manufacturing standard ID aircraft, type certificated unmanned aircraft, and broadcast modules.

- September 15, 2023, FAA issued a statement saying “FAA will exercise its discretion in determining how to handle any apparent noncompliance, including exercising discretion to not take enforcement action, if appropriate, for any noncompliance that occurs on or before March 16, 2024—the six-month period following the compliance deadline for operators initially published in the Remote Identification of Unmanned Aircraft final rule, RIN 2120-AL31. The exercise of enforcement discretion herein creates no individual right of action and establishes no precedent for future determinations.”

- September 16, 2023, deadline for everyone to comply with the remote ID regulations.

Major Changes from Proposed Rule to Final Rule

- Network-based / Internet transmission requirements have been eliminated. The final rule contains Broadcast-only requirements.

- UAS operators under the Exception for Limited Recreational Operations may continue to register with the FAA once, rather than registering each aircraft. However each Standard UA or Broadcast Module serial number must also be entered into the registration record for the unmanned aircraft.

- ‘Limited Remote ID UAS’ has been eliminated and replaced with Remote ID Broadcast Module requirements to enable existing UA to comply.

- FRIA applications may be submitted to the FAA beginning 18 months after the effective date of the rule, and applications may be submitted at any time after that

- Educational institutions may now apply for FRIAs as well as community-based organizations.

Remote Identification Risk Assessments

I couldn’t find any FAA risk assessment for Remote ID anywhere. They aren’t on the docket or on the FAA’s website. We even received 2 “no records” determinations to FOIA requests. (I redacted the names and addresses)

No Records Determination for FOIA Request 1

No Records Determination for FOIA Request 2

Aviation Attorney. FAA Certificated Commercial Pilot and Flight Instructor (CFI/CFII). Contributor at Forbes.com for Aerospace and Defense.